PART ONE: THE INTRODUCTION

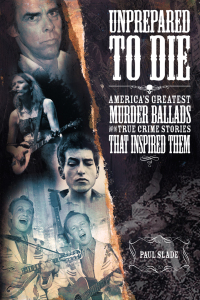

One look at Paul Slade’s web-site (Planet Slade) is all you’ll need to understand the author of the new tome, UNPREPARED TO DIE: AMERICA’S GREATEST MURDER BALLADS AND THE TRUE CRIME STORIES THAT INSPIRED THEM. You will see that Paul is not only one of the busiest men in the realm of journalistic endeavor, he is also one of the most inquisitive; that innate need to know has taken the man down some very dark backroads and alleys, into the sewers of London and the very bowels of England’s Parliament; that need to know has forced this gentle being to explore the warped psyches of criminals and vicious murderers. The time and effort put into researching the subject matter for his essays (which fall into three basic categories: “Murder Ballads,” “Secret London” and “Miscellany,” which Slade describes as “anything else I damn well feel like including”) is a full time job in itself; turning that research into entertaining pieces on significant or historic events is an art form. Working and living on Planet Slade led Paul to the idea of turning the “Murder Ballads” page of the site into a book on the subject. And, now, without further ado, we’re off to visit Planet Slade to discuss, among other things, Paul’s new book (the interview was conducted via e-mail; Iv’e kept intact the original English spellings from Paul’s replies)…

PART TWO: THE INTERVIEW

THE MULE: Paul, thanks for the great book and for taking the time to answer a few questions. First, let’s get into a bit of personal history. You’ve been a journalist for nearly 35 years. What led you down this path? Where did you start your journalistic career and what were the first stories you covered?

PAUL: When I finished my Business Studies degree in 1980, I had no idea at all how I wanted to make a living. The Watergate affair of the early 1970s had left me with a rather romantic view of journalism and I’d always enjoyed writing, so that was one of the very few areas that appealed to me, but I had no idea how to go about making that dream a reality. Then I stumbled across the media recruitment ads which THE GUARDIAN carried once a week and realised for the first time that it was possible to apply for entry-level reporters’ jobs on magazines and newspapers all over the UK.

I spent the next six months or so applying for any job in that section that looked remotely feasible and eventually struck lucky at CHEMIST AND DRUGGIST, a weekly trade magazine for retail pharmacists. They took me on to write a couple of pages of business news every week and that’s where I got my start. I was reporting company results, industry rows, boardroom changes and that kind of thing. The editor there drilled the basics of good journalistic practice into all his young team, so it proved a very good foundation.

I spent four years on C&D, then got a job on a new launch called MONEY MARKETING, which took off very rapidly and won several awards. That led to some freelancing for the nationals’ personal finance sections and the occasional bit of freelance music writing. Gradually, I managed to shift my output more towards the popular culture journalism I really wanted to do, and PlanetSlade followed in 2009.

THE MULE: I’ve been listening to music – including several of the songs chronicled in UNPREPARED TO DIE – for a very long time and, I must admit, the term “Murder Ballad” was unknown to me until Johnny Cash’s AMERICAN RECORDINGS version of “Delia’s Gone.” Can you give the readers a quick definition of the term and a brief history of the oral and lyrical traditions involved?

PAUL: I suppose a murder ballad would be any song which tells the story of an unlawful homicide – whether that story is fact, fiction or a mixture of the two. That’s a very wide field, though and I knew I’d have to adopt a tighter definition for my own work if I was ever going to do more than scratch the surface of any given song. Hence, I limit myself to those songs which tell the story of an identifiable real murder. I also decided to concentrate on songs which had been covered many times by many different artists, as these varying interpretations add an interesting extra dimension to the song’s history.

I always envisage this process as roping off a single square of turf in an enormous meadow and digging down as deep as I can in that one area alone. If I tried to excavate the entire meadow, I’d never penetrate more than an inch or two below the surface, which would not be very satisfying for either me or my readers.

Although the word’s used much more loosely these days, a ballad is actually a strict poetic form with its own rules – just as a sonnet or a limerick is. The basic structure is provided by alternating three-beat and four-beat lines, with the second and fourth lines of each verse rhyming. The opening verse of “Knoxville Girl” is a good example and here it is with the beats marked:

I met a little girl in Knoxville,

That town we all know well,

And every Sunday evening,

Out at her house I’d dwell.

The ballad form is fairly bursting with narrative momentum, which makes it an excellent way of telling a story. In the case of that “Knoxville Girl” verse, we’re only four lines into the song, but the story’s already well underway and we’re anxious to find out what happens next. The words’ steady rhythm means they’re half-musical already and easy to remember, so small wonder written ballad verses are so often transformed into songs. Whether used by the gutter poets of the Victorian age or by great artists like Coleridge and Wilde, the ballad form is irresistible.

Murder stories aren’t the only ones ballads tell, of course, but it’s only natural that this form should have been selected when 17th, 18th and 19th century British people had a murder tale to tell. Printed ballad sheets telling the killer’s story were sold at public hangings all over Britain until around 1850 and sometimes sung by the sellers to advertise their wares. The most popular sheets sold well over two million copies.

Folk singers have always loved the ballad form too, and are never happier than when a good juicy murder is the ballad’s subject. Traditional songs like these are polished by each new generation of singers which adopt them, constantly editing the song till only the core of the story and its most memorable images remain.

Many of the classic American murder ballads have their roots in much older British songs recording real murders. Early settlers took these songs with them across the Atlantic, later adapting them to their new surroundings. “Knoxville Girl” traces directly back to a British ballad called “The Bloody Miller,” which was written around 1683. “Pretty Polly” began life as a British ballad called “The Gosport Tragedy,” which dates back to the first half of the 19th century. In their new Americanised form, these songs retain not only their ballad structure, but also much of the language and imagery coined by their original versions – sometimes word-for-word.

Just as happened in Britain, the American songs were taken from town to town by travelling musicians. Home-grown American ballads could be used to spread news from one isolated rural community to another. This was a time long before radio, remember, when even those people who could read might have access to a newspaper only on their monthly trips to the nearest town. Ballads were sung to tell all kinds of stories, but a good sensational murder always been hard to beat for grabbing the audience’s attention. Murder songs’ appeal springs from the same quirk in human nature which makes us watch cop shows on TV or read true crime stories in tabloid newspapers.

THE MULE: How much of your previous work can be seen as a genesis for the material in UNPREPARED TO DIE and on your website, planetslade.com? Where did your interest in the murder ballad genre originate? Which song, in particular, fueled that interest?

PAUL: I’d done odd bits of writing for the music press before turning my attention to murder ballads, but nothing that involved analysing individual songs in any depth. That’s about the extent of the heritage as far as subject matter is concerned. More important were the skills and good habits I’d picked up in journalism of all kinds. This work had taught me the importance of getting my facts right, given me the research experience to chase those facts down and allowed me to hone my writing to a point where I could articulate exactly what I wanted to say in a clear, gripping and entertaining way.

I think I also benefitted from the fact that I’m old enough to have worked for many years in the pre-internet era. Where younger writers might assume any information that’s yet to be digitised simply doesn’t exist, I knew to dig deep among the dusty book shelves of Britain and America’s bricks-and-mortar libraries too. For all the convenience of Google, there are vast swathes of human knowledge which remain stored on paper alone, and my advanced age meant I was lucky enough to realise that.

I can think of three things which got me started seriously researching murder ballads and they all date from the noughties. Two of these three prompts directly involve “Stagger Lee,” so I guess I’d have to say that was the single most important song which drew me in.

It all began when I heard the radio DJ Andy Kershaw mention on his BBC Radio 3 show that he collected recordings of “La Bamba.” The idea of collecting one particular song in this way appealed to me, so I began collecting different recordings of “Stagger Lee.” I can’t remember why I settled on that particular song, but I’m sure Nick Cave’s stunning 1996 version of it played a part. Also, I already knew there were an awful lot of recordings of “Stagger Lee” to collect, which made finding as many as possible of them an intriguing challenge. The internet was then still in its infancy, so hunting out obscure records hadn’t yet become too easy to provide any satisfaction.

About a year later, I bought THE EXECUTIONER’S LAST SONGS, a 2002 Bloodshot Records compilation put together by Jon Langford of the Mekons. He’d taken the album on to raise funds for a death penalty moratorium project in Illinois. Langford’s approach was to team the best of our era’s Americana performers with classic murder ballads of all kinds: “The idea was to use death songs against the death penalty”, he told me.

The album’s highlights include Steve Earle’s version of “Tom Dooley,” the Handsome Family’s take on “Knoxville Girl” and Neko Case doing “Poor Ellen Smith.” Hearing so many great versions of these ballads on a single album got me thinking about the songs much more deeply and noticing the strands they had in common. Often, the killer’s logic seemed to be, “I love you, therefore I must kill you” and that stuck in my mind. What an odd way to look at the world.

Fast forward now to San Francisco in 2003, where I was enjoying a holiday. I spent one afternoon there mooching around in the basement music section at City Lights, the legendary counter-culture bookstore, where I found a copy of Cecil Brown’s STAGOLEE SHOT BILLY, a book telling the true story behind “Stagger Lee” itself. Reading that in a bar the same evening, I understood for the first time that many of the classic murder ballads were based on real crimes – and that those crimes were often recent enough to be researched in the newspaper archives. I started writing about murder ballads on my website a few years after that, and it’s those essays which eventually led to the book.

THE MULE: Your research into the eight ballads included in the book is painstaking. How long did the research into the true facts in this collection take? The murder ballad seems to be, primarily, a phenomenon of the American South. Did the origins of one tale prove more difficult to trace than the others? Did you discover information about these eight stories that surprised you?

PAUL: It’s hard to put a firm timescale on this. I started researching murder ballads properly in 2009, when I was getting PlanetSlade started, and finally published my book at the end of 2015. I was doing all sorts of other writing throughout those six years as well, though.

The bulk of my early work on murder ballads went into PlanetSlade’s essays (but again proved very useful when the book deal came up). Whenever I could manage a vacation trip to the US, I chose a city with links to one of my chosen ballads, where I’d spend a few days visiting the murder scene and all the relevant graves. These trips took me to Saint Louis, Cincinnati and Indiana.

Writing the book ate up most of 2015, though I took a month away from the keyboard for one final research trip. The area around Winstom-Salem and Charlotte seems to be “Ground Zero” for the killings that inspire songs like these, so I gave myself three solid weeks in North Carolina researching “Tom Dooley,” “Poor Ellen Smith” and “Murder of the Lawson Family.” As on all my research trips, I took the opportunity to interview local historians and musicians there, as well as to walk the killers’ own streets and make them as real as I could in my own mind.

On my way down to North Carolina, I paused in New York for a meal with the country singer Laura Cantrell, who I knew was particularly interested in “Poor Ellen Smith.” Laura gave me some useful clues on the song’s origin, but I had a lot of difficulty tracing these back to the song’s birth. With the book’s deadline looming, I’d resigned myself to admitting this failure in print. I did decide on one final plunge into the newspaper archives before giving up altogether, though, and this time a lucky chance produced exactly the information I needed. A few hours later, I had not only found the 1893 article which printed this song’s first-ever lyrics, but also identified the jailbird mule thief who wrote them. That was a very satisfying moment.

There were surprises in the research for every song. I’d had no idea how deeply the “Stagger Lee” killing was embroiled in Saint Louis’ party politics, for example, with Republicans determined to see the killer hang and Democrats lobbying for his early release. The central role syphilis played in “Tom Dooley’s” murder of Laura Foster came as a shock too, as did the revelation that “Pretty Polly’s” parent song was so closely tied to Britain’s Royal Navy. I hadn’t known that “Frankie and Johnny’s” Frankie Baker had sued two Hollywood studios over distorted adaptations of her song’s story either – let alone that she’d dragged Mae West into one of those actions.

THE MULE: Obviously, this book was not written in a day or two. From the time the idea came into your head ’til you finished it, how long did you work on this project? Did your research and work extend to other ballads? Would you be interested in working on a sequel?

PAUL: As I said above, I’d been researching murder ballads – at least intermittently – ever since 2009. The bulk of the book’s work got done in 2015, though. I started writing it in February that year and delivered the finished manuscript six months later.

It was a fairly tight deadline, so I had to keep all my focus just on the eight songs covered in the book, which are “Stagger Lee,” “Frankie and Johnny,” “Knoxville Girl,” “Tom Dooley,” “Pretty Polly,” “Poor Ellen Smith,” “Murder of the Lawson Family” and “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll.” I was determined to interview at least one relevant musician for each of the songs, which gave me a good excuse to arrange conversations with favourite songwriters like Billy Bragg, Dave Alvin and the Bad Seeds’ Mick Harvey.

I do have one idea for a follow-up book, this one looking at the British gallows ballads which were sold at public hangings, but it’s a bit too early to talk about that.

THE MULE: The psychology behind these acts is as interesting as the stories and historical references. Was there one story that caused you to reevaluate your stance, once you researched the psychological aspects of the parties involved?

PAUL: There was one song that really got to me, but it’s one I wrote about on my website rather than in the book. It’s called “Misses Dyer, the Old Baby-Farmer” and it tells the true story of a woman in Victorian London who took in disgraced girls’ illegitimate babies, promising to give them a home. As soon as she had the money the girl paid her for this service, she’d simply stifle the baby and dump it in the Thames. This happened at the end of the 19th century and she’s thought to have murdered more than 40 babies in all.

I spent about a week researching this squalid, nihilistic tale and writing it up. By the time I’d finished I had a very bleak view of the human race and just wanted to scrub my brain clean of the whole tale. I often wonder how spending a full year or 18 months immersed in the life of a serial killer must affect the writers of these people’s biographies. Inviting Jeffrey Dahmer into your head to write a book about him is one thing, but persuading him to leave again when the job’s done may not prove so simple.

THE MULE: I was surprised to learn that both “Stagger Lee” and “Frankie and Johnny” were based on events from just across the Mississippi from my home. The story of Frankie Baker, in particular, touched something inside me…. the fact that at least three movies have used the lyrics, or simply the song title, as a jumping off spot for their script, but her real story has never been told in any meaningful way. Why do you believe her story remains largely unknown?

PAUL: I think the fact that the song’s twice been a chart hit – once for Elvis Presley and once for Sam Cooke – has worked against the real story. Neither of these chart versions bear any resemblance to what really happened, and all the movie adaptations just create further confusion. In Presley’s version, Frankie’s a singer working the Mississippi riverboats, in Sam Cooke’s she’s rich enough to buy Johnny a sports car and in Mae West’s 1933 film she marries an FBI agent. Plus, of course, she’s always a white woman.

The real story – young black sex worker kills her pimp in self-defence – is far more interesting than any of these sanitised versions, but it’s been obscured by so many distortions over the years that the genuine Frankie Baker gets lost.

The quote from Frankie herself that lingers most strongly with me came when she was protesting yet another cavalier Hollywood treatment of her story and the unwelcome attention which these films always brought. “I know that I’m black, but even so I have my rights,” she pleaded to one reporter. “If people had left me alone, I’d have forgotten about his thing a long time ago.” The humility and resignation of that remark breaks my heart every time I hear it.

THE MULE: Aside from your very entertaining pieces at PlanetSlade, what future works can we expect to see from the mind and desk of Paul Slade?

PAUL: I’m working on a new PlanetSlade essay at the moment, which springs from a very interesting artefact I recently discovered. It was made to commemorate a real 19th century US murder of the 1880s and, like all the best objects of this kind, leads anyone researching it into some very interesting tangents and unexpected discoveries. I don’t want to say anything more about that piece for the moment, but it looks set to keep me busy for at least the next month or so. After that, who knows?

PART THREE: UNPREPARED TO DIE

(Paul Slade; 290 pages; SOUNDCHECK BOOKS, 2015)

Let me begin by stating, “What a great read!” Most of us have heard at least one version of at least one of the eight ballads discussed in UNPREPARED TO DIE, whether it be the Kingston Trio’s “Tom Dooley” or Sam Cooke’s “Frankie and Johnny.” I hadn’t heard the term “Murder Ballad” until it was used in reference to “Delia’s Gone” from Johnny Cash’s AMERICAN RECORDINGS in 1994; I certainly didn’t know that tunes so named were based on actual killings (after reading Slade’s book, it’s kinda hard to call some of the cases “murder”). Maybe it was because songs like “Frankie and Johnny,” “Stagger Lee” and “Tom Dooley” were such fixtures on radio and television and in the movies when I was a kid that I never really paid much attention to the dark stories told through the lyrics. Whatever the reason, those tunes were simply background noise in my youth, with a melody so stunningly simple yet so immediately captivating that they ended up getting lodged in the old brainpan and tended to make their way to the top of my internal playlist at the oddest times. I now have a deeper understanding of where those songs originated and more than a passing respect for the original balladeers and the musicians who have kept the songs alive for so long… in some cases several hundred years.

Slade’s writing throughout these eight essays, while scholarly in its depth, is very conversational in its delivery. In other words, he manages to get to the heart of the matter with decades (or centuries) old facts without boring the reader. As it turns out, the least compelling story is the one surrounding Bob Dylan’s “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,” which tells of the sadistic murder of a 51 year old barmaid in Baltimore in 1963, the year Dylan wrote the song. Miss Carroll was black, her attacker was a wealthy and arrogant white man. While reading Slade’s account and history of the brutal act, as well as the grossly inappropriate sentence meted out to her attacker, one thought that ran through my mind was, “None of this right! This should never have happened,” but, I also thought, “Let’s get back to some more of those hundred-year-old cases.” I hate to say it, but… it appears that Hattie Carroll’s murder was just too recent and too mundane to keep my interest. Obviously, though, it piqued enough interest in both Dylan and Slade to be the subject of a song and a chapter in UNPREPARED TO DIE.

The other pieces, “Frankie and Johnny” and “The Murder of the Lawson Family” in particular, really managed to keep me involved in the stories of both the victims and the killers. In the case of Frankie Baker, who was charged with murdering her boyfriend, Allen Britt, for “paying attention to another woman,” the song is far more famous than the actual Saint Louis case. The song actually led to Miss Baker leaving Saint Louis, settling first in Nebraska, then moving on to Oregon; it seems that wherever she went, the song and the rumors followed. It’s amazing that, in the nearly 120 since Frankie killed Allen, at least three different movies (one starring Mae West, another Elvis Presley) have been produced based on the “Frankie and Johnny” song, but not one has bothered to tell the real story. “The Murder of the Lawson Family” is a gruesome tale of mental illness, probable incest, a guilty conscience and – after the fact – unimaginable greed. On Christmas Day, 1929, North Carolina tobacco farmer Charlie Lawson slaughtered his wife and six of their seven children before killing himself. Slade’s examination of the case presents several possible scenarios for what led to such a very bloody Christmas present, including an earlier brain injury and an incestuous rape of the Lawson’s oldest daughter. The latter theory posits that Lawson’s wife, Fannie, had discovered that daughter Marie was pregnant and that Charlie was his grandchild’s father. These and other factors led to a perfect storm of despair in Charlie’s mind, leaving only one solution. Several moneymaking schemes from Charlie’s brother and nephew after the tragedy are nearly as grotesque as the actual killing spree.

Along with the retelling of events for each of the eight killings (more than a few are of the jealous rage or “you done me wrong” variety), are interviews with historians and, more compelling, many of the musicians responsible for keeping the “Murder Ballad” alive as a viable musical genre. Insight into the art form and the songs themselves is offered from Dave Alvin, Billy Bragg, Laura Cantrell and others. Following each chapter is a list of ten of the most iconic versions of the song discussed therein, dating from the early 1920s through to some of the most recent versions, performed by many of the musicians interviewed for the book. And, like most good releases nowadays, UNPREPARED TO DIE includes several bonus features, which can be found here. The bonus material includes additional thoughts from the various musicians on each song, the genre in particular and much more (like Dave Alvin’s musings regarding killer bees), as well as play lists for each chapter. Whether you’re a music fan, a history fan or a true crime fan, UNPREPARED TO DIE should be right up your dark alley. UNPREPARED TO DIE: AMERICA’S GREATEST MURDER BALLADS AND THE TRUE CRIME STORIES THAT INSPIRED THEM is available directly from Soundcheck Books, Amazon or any of the usual outlets.